Puerto Rican cuisine, or cocina criolla, is a vibrant culinary tradition shaped by centuries of cultural blending. Its flavors reflect the island’s indigenous Taíno roots, Spanish colonization, and African influences, later enriched by Chinese, Middle Eastern, and American elements. This fusion has created a unique gastronomic identity that remains deeply rooted in tradition while continuing to evolve.

Rich, bold, and comforting, Puerto Rican food is defined by slow-cooked stews, marinated meats, and the widespread use of sofrito, a fragrant blend of garlic, peppers, onions, and herbs. The island’s tropical climate provides an abundance of fresh ingredients—plantains, root vegetables, seafood, and pork—all of which play a central role in its cuisine. Food is more than sustenance; it is the heart of celebrations and communal gatherings, a reflection of history and shared joy.

The culinary landscape of Puerto Rico has evolved over time, incorporating modern influences while staying true to its roots. The first restaurant, La Mallorquina, opened in Old San Juan in 1848, marking the formalization of Puerto Rican dining culture. The island’s first cookbook, El Cocinero Puerto-Riqueño o Formulario, was published in 1859, capturing the recipes and traditions of the time.

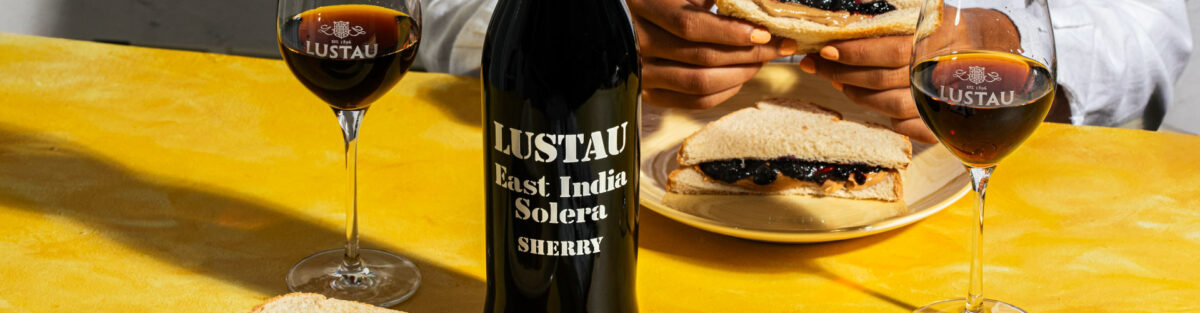

Pairing such dynamic cuisine with wine might seem like a challenge, but few wines possess the complexity, range, and versatility of sherry from Jerez. From the crisp, saline notes of Manzanilla to the rich, nutty depth of Oloroso, to the sweeter both varietal and blended styles, sherry wines enhance and complement Puerto Rican flavors in ways that other wines often struggle to achieve.

THE CULINARY HERITAGE OF PUERTO RICO

TAÍNO INFLUENCE: THE ISLAND’S FIRST COOKS

Before Spanish contact in 1493, Puerto Rico was inhabited by the Taíno people, who relied on fishing, hunting, and farming. Their diet, rich in plant-based and protein sources, remains central to Puerto Rican cuisine today. Root vegetables, collectively known as viandas, were staples in their diet, including cassava (yuca), tannier (yautía), sweet potato (batata), and sweet corn root (lerén). These ingredients are still widely used in traditional Puerto Rican dishes.

The Taínos introduced barbacoa, a slow-cooking method over a raised wooden platform that heavily influenced what is now known as barbecue. While the Taínos primarily used this technique for roasting fish and small game, it later evolved into the preparation of lechón asado, Puerto Rico’s famous whole-roasted pig. They also cultivated a variety of spices, herbs, and tropical fruits such as allspice, avocado, papaya, guava, and soursop, many of which continue to be essential in Puerto Rican cooking today.

A few key elements in Taíno cooking:

· Cassava (Yuca): One of the primary starches, used to make casabe, a thin, crunchy bread.

· Corn (Maíz): Though not as dominant in Puerto Rican cuisine as in Mexico, corn was still a staple, often used in porridges and tamales.

· Achiote (Annatto): A vibrant red-orange spice that gives Puerto Rican dishes their signature golden hue.

· Barbacoa: The Taíno method of slow-cooking meats over an open flame, which heavily influenced lechón asado (roast pork).

· Ají Dulce and Peppers: The foundation of flavor in many Puerto Rican stews and sauces.

· Coconuts, Guavas, and Pineapples: Tropical fruits used in drinks, desserts, and sauces.

SPANISH INFLUENCE: EUROPEAN FLAVORS TAKE ROOT

The arrival of the Spanish in the 15th century dramatically expanded Puerto Rico’s culinary landscape. Spanish settlers introduced key ingredients such as rice, olives, capers, pork, and legumes, which became staples in dishes like arroz con gandules and asopao. Chorizo, a Spanish sausage, remains integral to Puerto Rican cuisine, incorporated into dishes such as arroz con pollo and asopao con chorizo.

One of the most enduring Spanish contributions is sofrito, an aromatic base for many Puerto Rican dishes. While originally brought from Spain, the island’s version evolved to incorporate native and African ingredients, making it distinct from its European counterpart. Spaniards also introduced new cooking techniques, such as frying. The use of lard became prevalent, leading to fried delicacies like tostones (fried plantain slices) and bacalaitos (salt cod fritters). Additionally, the Spanish brought pastelón, a plantain-based dish reminiscent of Italian lasagna, showing how European influences were adapted to local ingredients.

Spanish influence is also evident in Puerto Rico’s panaderías, which were first established by settlers and continue to serve as community hubs. Traditional pastries such as flan, brazo gitano, and mallorcas originated in Spain but have since evolved into uniquely Puerto Rican variations. Mallorcas, introduced by immigrants from the Balearic Islands in the 1800s, are an example of how European baking traditions adapted to the tropical climate, resulting in a slightly denser, sweeter bread than its Spanish counterpart.

Spain’s influence is perhaps the most prominent in Puerto Rican cuisine, as seen in the island’s love for rice, pork, and stews:

· Rice & Legumes: While rice was already known to the Taínos, the Spanish introduced more refined cultivation techniques and began pairing it with beans and other legumes, creating dishes like arroz con gandules (rice with pigeon peas).

· Pork & Cured Meats: Spaniards introduced pigs to the island, leading to lechón asado, longaniza (sausage), and various pork-based stews.

· Olives & Capers: These Mediterranean ingredients became essential in Puerto Rican stews, giving dishes a briny depth of flavor.

· Wine & Vinegar: The Spanish love of wine extended to the American territories, though sherry and other wines from Spain were primarily used for cooking or religious purposes.

· Sofrito: A direct adaptation from Spain, sofrito is the aromatic base for many Puerto Rican dishes. However, it evolved on the island to include indigenous and African ingredients, creating a unique version distinct from Spanish sofrito.

AFRICAN INFLUENCE: BOLD SPICES AND COOKING TECHNIQUES

During Spanish rule, enslaved Africans brought their own culinary traditions, adding depth and complexity to Puerto Rican cuisine. Their influence is particularly evident in the widespread use of plantains, coconut, and root vegetables, as well as slow-simmered stews and boldly spiced dishes.

Africans transformed the indigenous Taíno burén (a ceramic cooking tool used to make casabe, a yuca-based flatbread) into an iron griddle, allowing for the preparation of coconut-based candies and dishes like mondongo, sancocho, and cazuela. Many beloved Puerto Rican dishes, including mofongo, and pasteles, trace their origins to African culinary traditions.

Essential ingredients such as plantains, pigeon peas, annatto, and orégano brujo were introduced through the transatlantic slave trade. The African practice of braising meat, fish, and vegetables—known as guisadas—evolved into Puerto Rican favorites like pollo guisado, bacalao guisado, and bean stews thickened with squash and ham.

· Plantains & Bananas: While plantains existed in Puerto Rico before Spanish rule, African cooking cemented their role as a staple, leading to dishes like mofongo and pastelón.

· Coconuts: Though already present in Taíno cuisine, Africans further integrated coconut into both savory and sweet dishes, including tembleque (coconut pudding) and pitorro (Puerto Rican moonshine).

· Fritters & Fried Foods: Many of Puerto Rico’s favorite fried snacks, such as alcapurrias (stuffed fritters) and bacalaitos, have African roots.

· Stews & Soups: African cooking emphasized slow-simmering dishes, which influenced Puerto Rican favorites like asopao (hearty rice stew) and sancocho (meat and root vegetable stew).

The impact of African influence on Puerto Rican cuisine cannot be overstated. Seasoning blends became bolder, dishes became heartier, and a deeper appreciation for plant-based staples, like root vegetables and legumes, emerged.

SHERRY WINES AND PUERTO RICAN CUISINE: A NATURAL PAIRING

Sherry wines are the perfect match for Puerto Rican cuisine due to their remarkable versatility and depth of flavor. The saline edge of fino and manzanilla sherries pairs beautifully with briny, fried, and seafood-based dishes, enhancing their freshness. amontillado and oloroso, with their oxidative aging, develop nutty and caramelized notes that complement the slow-roasted, spiced flavors of Puerto Rican meats. The luscious richness of pedro ximénez and moscatel balances the tropical sweetness found in plantain-based dishes and desserts, creating a harmonious contrast. Additionally, sherry’s bright acidity and structured profile cleanse the palate, making it an excellent companion for fried foods, stews, and other hearty dishes. Just as Puerto Rican cuisine is a fusion of cultures, sherry wines from Jerez have evolved over centuries, influenced by Spanish, Moorish, and Roman traditions. Both share an emphasis on diversity, and bold flavors, making them a perfect match:

· Fino & Manzanilla – Their crisp, saline qualities pair beautifully with briny, fried dishes like bacalaitos and tostones.

· Amontillado – Its nuttiness complements the garlicky richness of mofongo and the depth of arroz con gandules.

· Oloroso – With its oxidative caramel notes, it enhances the smoky, spiced flavors of lechón asado.

· Pedro Ximénez & Moscatel – Their luscious sweetness balances desserts like tembleque and caramelized plantains.

Both rely on patience, and complex flavor profiles:

· Slow-Cooked & Aged: Puerto Rican dishes like lechón asado and asopao develop flavor over time, much like Sherry’s meticulous solera aging system.

· Rich & Bold Flavors: Puerto Rican food is known for its intensity—whether it’s the garlic punch of mofongo or the deep umami of gandules. Sherry, with its oxidative, nutty, and saline elements, complements these flavors effortlessly.

· Sweet-Savory Balance: Many Puerto Rican dishes play with sweetness (plantains, coconut, annatto oil) and savory ingredients making them an excellent match for the spectrum of sherry styles, from dry Fino to luscious Pedro Ximénez.

Sherry wines also serve as a base for tropical cocktails like PX Coquito, Sherry Piña Colada, and the Lechosa Cobbler, blending Puerto Rican flavors with the heritage of Jerez:

· PX Coquito – A holiday favorite with coconut milk, condensed milk, and Pedro Ximénez, replacing traditional rum.

· Sherry Piña Colada – A sophisticated twist on the classic, using Amontillado for a nutty depth.

· Lechosa Cobbler – A take on the Sherry Cobbler, incorporating papaya and nutmeg for a tropical feel.

By understanding Puerto Rico’s culinary history, we can see why Jerez wines aren’t just an excellent pairing—they are a natural extension of the island’s deep-rooted gastronomic traditions. Pairing the two creates an experience that celebrates cultural heritage while allowing for new, exciting culinary innovations.