It’s that time of the year when data on the recent harvest is available and top of mind. Once again, we share input, developments, and the general impact of the 2023 grapes collected.

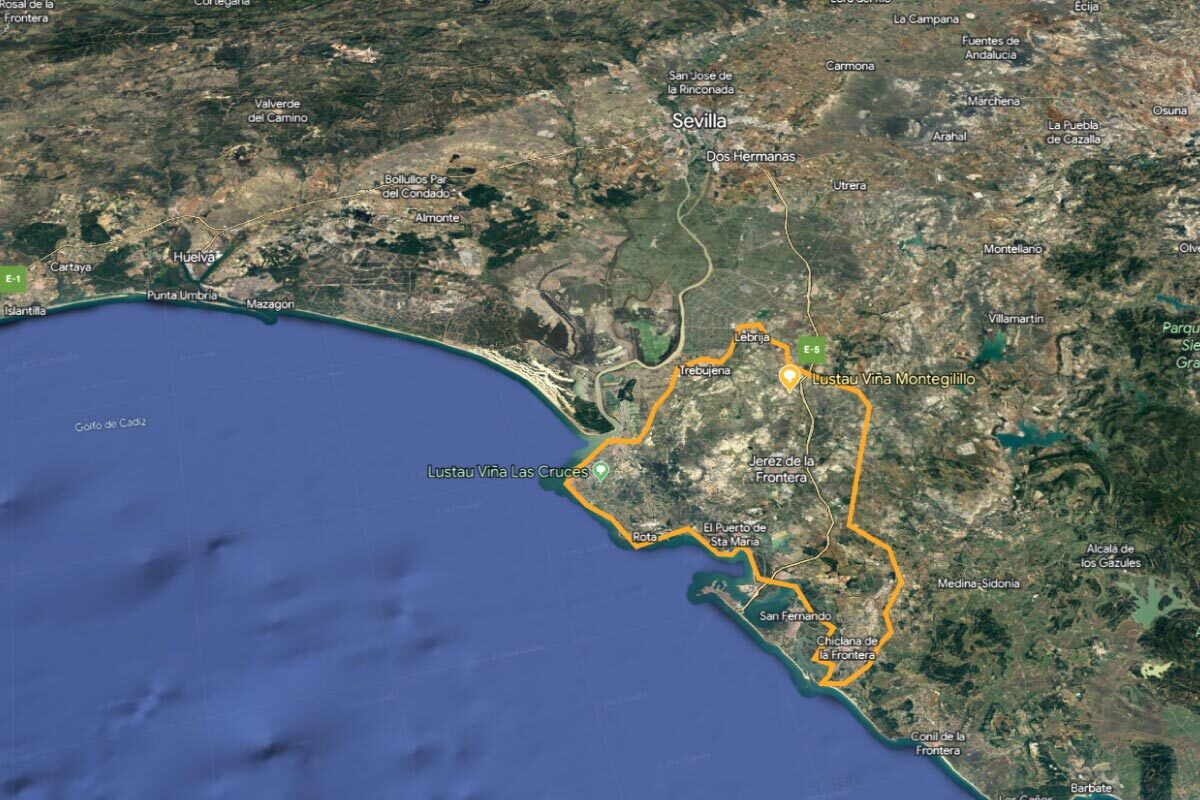

First let’s describe and assess the area, the Marco de Jerez is the southernmost winegrowing region on the European continent (the town of Jerez sits on latitude 36º North). It is located on the northeast side of the Cádiz province in southern Spain, very close to the Strait of Gibraltar. Because of this low-lying latitude, the prevailing climate of Jerez is warm. Summers are dry and marked by high temperatures, frequently rising above 40ºC (104ºF). The region enjoys between 3,000 and 3,200 hours of effective sunlight. The proximity of the Atlantic Ocean has an important role in maintaining humidity levels and moderating the temperatures, something that is more evident at night. The highest-altitude vineyards are found at around 150m (492ft) with the average being at 45 m (148ft). Consequently, fully ripening the grapes every vintage year should not be an issue.

There is no set date to signal the start of the harvest given that it all depends upon the ripeness of the grapes, which should be at least 10.5º Baumé (potential alcohol). The growers usually lean toward harvesting as early as possible to avoid the potential of untimely rains spoiling the grapes. Winemakers, however, have more precise needs regarding the ripeness of the grape, degree of acidity, and general health. Once the event starts, the grapes must always reach the pressing machines as quickly as possible, and in the best possible condition. This year, the average has been 11.67 Baumé units, also higher than the one obtained in 2022.

A total of 31 wineries registered with the Regulatory Council have processed a total of 49.9 million kilograms of grapes to produce wines and vinegars under the designations of origin Jerez-Xérès-Sherry, Manzanilla – Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and Vinagre de Jerez. This quantity represents an increase of more than 12.3% compared to the 44.4 million from the previous year, although it should be noted that the 2022 harvest was particularly short. Once more, the harvest has been marked by a scarcity of rainfall throughout the year. Precipitation in the different areas of the designation of origin ranged between 425 and 480 liters per square meter, well below the 600 liters of a normal year. These rains were concentrated mainly in the months of December and January, although in June, another 40 – 50 liters fell, helping to alleviate the soil’s water shortage.

The grape harvest in the sherry region always begins in the inland vineyards, which reach their optimal ripeness level early, while vineyards near the coast are usually harvested well into the month of September. As it is a custom, the first winery to acknowledge the quality of the crop was Lustau which was responsible for kicking off the 2023 harvest at Montegilillo Estate, in the northern border of the municipality of Jerez de la Frontera, on August 3rd.

For Lustau in particular, this is what the current campaign looks like:

• Harvest dates by grape variety:

Palomino: start 01/08/2023 – end 04/08/2023.

Moscatel: start 25/08/2023 – end 26/08/2023.

Pedro Ximénez: start and end on 29/08/2023.

• Yields and health level:

Palomino: Very healthy crop. Alcohol (11,8 Be). Excellent quality.

Moscatel: Healthy crop. Alcohol (14 Be). Excellent quality.

Pedro Ximénez: Very healthy crop. Alcohol (22 Be). Excellent quality.

INTERVIEW WITH BOTH CÉSAR SALDAÑA, PRESIDENT OF THE DO JEREZ, AND SERGIO MARTÍNEZ, LUSTAU CAPATAZ GENERAL.

Left: César Saldaña. Right: Sergio Martínez, Lustau Capataz General.

Q1- Despite the slight increase in kilos and the two-week delay in the start of the harvest compared to 2022, it seems that this year’s campaign is once again marked by the lack of rain, heatwaves, the constant advancement of grape harvesting, and the consistent decrease in production. Based on this trend of the last five years, can we openly say that climate change is already fully affecting the Jerez region? What official data do you have at the Council to support this trend?

César:

“Without a doubt. The most convincing sign is the advancement of the grape harvest, which now never starts later than the first week of August, whereas in the past, the grape harvest month was always September. However, this long-term – undeniable – trend has also combined in recent years with periods of very dry conditions, which has reached its fifth year in 2023. We have seen these drought cycles in Jerez in the past, such as the one we experienced in the years 1991 – 1995. We hope that rainfall returns to normal levels for the region in the upcoming campaign in this regard.”

Sergio:

“Clearly, climate change is a reality, and not only in the sherry region. Harvests exceeding 11,000 kilograms per hectare will be difficult to witness again… currently, a vineyard with ‘good yield’ is harvesting around 7,500 kilograms per hectare. You can check the data provided by the CR on its website, where you can observe a decrease in the yields obtained in recent harvests. Although, in particular, this year 2023 has been slightly higher (+12%), the trend over the last 5 years has been negative year after year (-20%).”

Q2- Alongside the regular environmental conditions of dryness and the decrease in the annual production average, there also seems to prevail a high health level of the grapes and a remarkable concentration of the harvest year after year. Can we speak of a widespread shift from quantity to quality? Is this something positive?

César:

“Indeed. Two factors have contributed to this. On one hand, even though the year has once again been dry in overall terms (barely 450 liters per square meter compared to the historical average of over 600 liters), it has rained at very opportune moments. First during the months of December and January, and subsequently in early June. Additionally, the month of July has been particularly mild, allowing for a very gradual grape ripening, without the heatwaves that characterized the 2022 harvest. Prevailing were westerly winds and frequent nocturnal dew, allowing the grapes to arrive healthy and with an adequate acidity/sugar balance at the time of harvesting. In these types of years, the quality of the soil also proves to be an absolutely critical factor for the final quality of the obtained musts.”

Sergio:

“If the vineyards are well cared for and maintained the consequences for the grape must are indeed very optimistic. From a health perspective, the grapes collected this year were spot on, resulting in a fermentation process without interruptions or contaminations, yielding exceptional base wines. Climate change affects the sherry region, but it doesn’t have to be negative if you take care of the vineyard. Now, the fact that there is a decrease in yields compared to other years, and this results in truly exceptional wines, doesn’t mean that the musts obtained with higher yields were of lower quality. Historically, all sherry musts from yields below 11,400 kilograms per hectare have been of very good quality (Jerez Superior origin).”

Q3- Does this trend in the recent harvest profiles accelerate decisions such as the possible use of irrigation, perhaps the expansion of vineyards (to counteract the decrease in production), or the focus on new grape varieties, among others?

César:

“For now, irrigation is something we only consider for extreme cases and in new plantations, aiming to ensure the plants’ survival. It is true that there is a debate, but I don’t believe that in our Designation of Origin (DO), there will be a general authorization for irrigation in the medium term. As for the expansion of vineyard acreage, it is highly limited in terms of planting rights, so I see it very difficult to have more hectares. However, everything that is uprooted is replanted. We no longer see vineyards being replaced by olive or almond trees. Finally, where I do believe we will see changes is in the gradual introduction of new/old grape varieties. That is, in the recovery of grape varieties that were used in Jerez before the Phylloxera. The new set of regulations already contemplates this, and there are reasons for its use. For example, there are varieties like Vigiriega that have a clearly longer cycle than Palomino, which is undoubtedly an advantage in the context of climate change, where the plant’s life cycles have been shortened.”

Sergio:

“It’s a difficult decision to make because it greatly depends on each vinegrower’s situation. If you expand the vineyard, you must increase the costs of proper vine care, knowing that the yield may not meet expectations, and the profits from selling grapes at the current price may not justify such an investment. The ‘new’ grape varieties are not as productive, and they generally yield less. On the other hand, if the use of irrigation were allowed, it might slightly dilute the quality of the must, so reasonable irrigation usage would be necessary. Additionally, not all vineyards have access to irrigation (there are not enough wells). Moreover, during periods of drought, allocating water for dry farming is not regulated. In my opinion, we should strive for a balance to ensure a yield of around 10,000 kilograms per hectare every year, excellent in terms of health and quality.”

Q4- Finally, do you believe there is any correlation between the type of pruning, along with the mechanization or lack thereof in harvesting, and the levels of production/quality?

César:

“It is evident that there are decisions made in the vineyard based on economic criteria, such as mechanization or double cordon pruning. But it is also true that there has been a lot of progress in improving these tasks and achieving high quality in this type of farming. Moreover, mechanization greatly facilitates night-time harvesting, which promotes the arrival of grapes in better conditions at the winery. In any case, the decision to maintain traditional practices like Vara y Pulgar pruning or hand harvesting is directly related to quality, without a doubt. Therefore, grapes from these types of traditionally-tended vineyards also command higher prices.”

Sergio:

“Of course, it takes time and experience to make the right decision because a multitude of factors influence the production/quality levels of a vineyard, including the type of pruning and how the harvesting is done (manual or mechanized). However, it all depends on how these parameters interact with each other. Climate, soil, type of pruning, mechanization, or lack thereof, etc., all have different effects depending on the age of the vines. To give you an idea, two vineyards with the same age, soil, and climate, based on the pruning method, can yield completely different results. But vineyards with the same pruning, soil, and climate can also yield different results depending on their age. The difficulty lies in ‘getting it right’ with the appropriate pruning for each vineyard, as there are factors, we cannot control, such as the weather.”