The idea that certain foods and wines are “meant to go together” has been a cornerstone of gastronomy for centuries. But what if those affinities were more than tradition — what if they were encoded at the molecular level? Welcome to the science of molecular pairing wine, a discipline that blends aroma chemistry, sensory analysis, and culinary intuition to reveal why certain pairings work so beautifully.

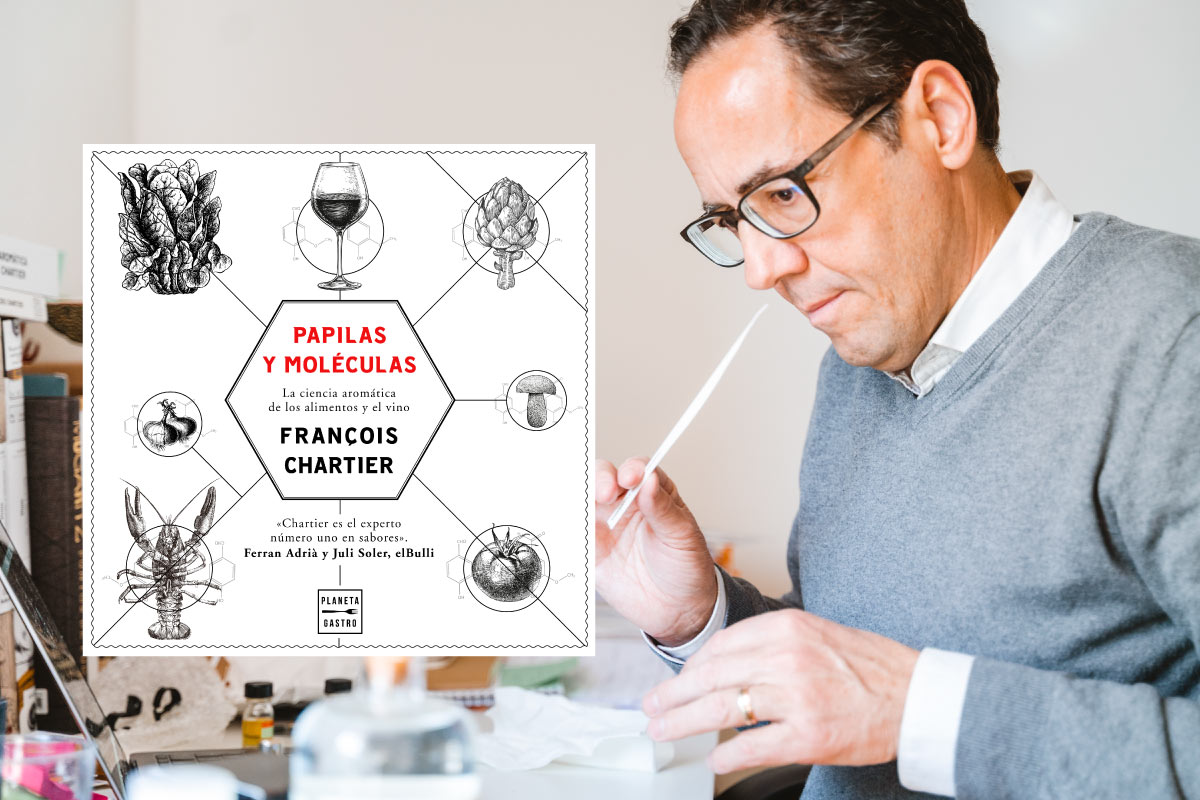

Among the pioneers of this approach is François Chartier, whose concept of “aromatic harmonies” has reshaped the way chefs and sommeliers think about pairing. His groundbreaking book, Taste Buds and Molecules (M&S 2009), introduced a generation of professionals to the aromatic building blocks that connect food and drink in surprising ways.

In this article, we’ll explore how molecular pairing applies to wine in general and to sherry wines in particular — one of the most aromatically complex categories of wines in the world. We’ll walk through the theory, trace Chartier’s influence, and discover how styles like fino, amontillado, or oloroso interact with food on a molecular level. This is your guide to the molecules that make pairings sing.

THE SCIENCE BEHIND MOLECULAR PAIRING

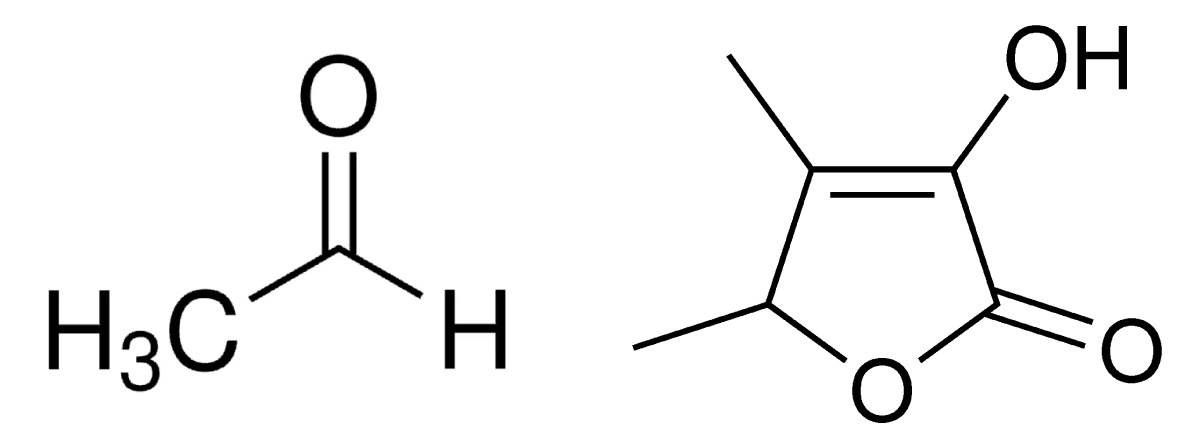

Why do some food and wine combinations feel almost magical, while others fall flat? The answer often lies not in tradition or intuition alone, but in chemistry. At the heart of molecular pairing is the study of aromatic molecules—the volatile compounds that shape how we perceive flavor through smell. These molecules don’t just define what we taste; they connect ingredients across categories in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

By identifying shared aromatic compounds between food and wine, we can move beyond trial and error to craft pairings that resonate on a sensory level. It offers a bridge between analytical data and the deeply human act of enjoying a meal.

WHAT ARE AROMATIC MOLECULES AND WHY DO THEY MATTER?

Aromatic molecules are the invisible threads that weave together the tapestry of flavor. They are volatile compounds—meaning they evaporate easily and reach our olfactory receptors—that define the scent and, by extension, the taste of both food and wine. In the world of gastronomy, their role is crucial: up to 80% of what we perceive as flavor is actually aroma, according to research in sensory science and food chemistry.

In wine, aromatic molecules arise from grape variety, fermentation, and aging. In sherry, for example, biological aging under “flor” yields high levels of acetaldehyde, responsible for the characteristic green apple and almond notes in fino. Oxidative aging, on the other hand, produces molecules like sotolon, which give amontillado or oloroso their nutty, savory complexity.

Understanding these aromatic markers allows sommeliers and chefs to recognize affinities between wine and food on a molecular level. It’s not just about pairing white wine with fish—it’s about matching shared molecules, like pyrazines, lactones, or furfurals, that echo each other across the plate and the glass.

FROM SENSORY ANALYSIS TO MOLECULAR MAPPING

Before the advent of advanced analytical tools, wine and food pairings were guided almost entirely by intuition, tradition, and experience. Sommeliers and chefs relied on sensory analysis—taste, smell, texture, and visual cues—to create harmony on the plate and in the glass. But while the human palate is sophisticated, it’s also limited by subjectivity and the natural variability of perception.

Today, scientific techniques like gas chromatography and mass spectrometry allow us to dive beneath the surface, revealing a deeper layer of flavor logic. These methods identify the volatile aroma compounds that define the aromatic DNA of ingredients and wines. As François Chartier describes, these tools are like “microscopes for flavor,” offering a precise map of the molecules that shape our sensory experiences. But it’s not just about data—Chartier reminds us that creativity still leads the way. Science gives us the map, but imagination charts the journey.

This shift—from tasting to mapping, from instinct to chemistry—has opened up a new frontier in food and wine pairing. It doesn’t replace tradition; it deepens it, giving professionals a way to explore beyond the expected while grounding their choices in molecular truth.

Credit: Consejo Regulador DO Jerez-Xérèz-Sherry

THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS A PERFECT PAIRING

Despite the precision of molecular analysis, it’s important to remember that no two palates are alike—and no pairing is ever universally “perfect.” Our perception of food and wine is shaped by a complex web of factors: cultural context, mood, memory, and even the setting in which the pairing is experienced. A molecular match might provide the scaffolding, but the emotional resonance completes the picture.

As François Chartier puts it, “science alone cannot explain why a dish moves us.” Aromatic molecules may provide the logic, but it’s our own lived experience that gives pairings meaning. The real beauty of molecular sommellerie lies not in prescribing fixed rules, but in offering new tools—ways to uncover why something works and to inspire bold, creative combinations.

Credit: Consejo Regulador DO Jerez-Xérèz-Sherry

Rather than limiting intuition, molecular pairing expands it. It empowers chefs and sommeliers to understand the ‘why’ behind tradition and to build new pairings that resonate both aromatically and emotionally.

FRANÇOIS CHARTIER AND THE BIRTH OF MOLECULAR PAIRING

Long before “molecular gastronomy” became a buzzword, François Chartier was quietly pioneering a different frontier—one that focused not on textures or transformations, but on the hidden aromatic bonds between ingredients. Crowned Best Sommelier in the World (Sopexa, 1994), Chartier spent decades bridging the gap between wine, science, and cuisine. His goal? To “democratize aroma science” and give chefs and sommeliers a practical, creative language for designing flavor harmony.

At the heart of Chartier’s approach is a deceptively simple idea: ingredients that share dominant aromatic compounds are predisposed to go well together. But what began as a theory has grown into a full-fledged discipline, supported by analytical tools like gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, and applied in contexts as diverse as fine dining, sake blending, and perfumery.

Today, Chartier continues his work from Chartier World LAB Barcelona, expanding the reach of his ideas into neuroscience, terroir mapping, and AI-assisted gastronomy. Yet the spirit remains rooted in the same foundational belief: that flavor is not just chemistry, but memory, culture, and emotion combined.

HOW MOLECULAR PAIRING ILLUMINATES SHERRY WINES

Sherry wines, with their wide stylistic range and intricate aging processes, are a playground for molecular sommellerie. Each style—from the delicate fino to the decadent pedro ximénez—displays a distinct aromatic profile shaped by “flor” yeasts, oxidation, solera blending, and time. These profiles are not abstract descriptors; they are built upon a foundation of volatile compounds that interact with our senses and with the foods we pair them with.

Go in depth with sherry’s outstanding diversity below:

François Chartier refers to sherry wines as “molecular treasures”—wines that carry aromatic signatures unlike any others, with compounds like acetaldehyde, sotolon, and phenolic aldehydes playing starring roles. By analyzing the dominant molecules in each style, we not only gain a deeper understanding of their complexity but also open the door to pairing them with uncanny precision. Below, we explore how molecular logic helps reveal the full potential of each category.

FINO AND MANZANILLA: FRESHNESS, FLOR, AND SALINITY

Fino and manzanilla are biologically aged under “flor” , the layer of yeast that protects the wine from oxidation and contributes a host of signature aromas. Acetaldehyde, the dominant compound, evokes notes of green apple, bruised almond, and chamomile—fragrant, nutty, and distinctly savory. Other key volatiles include ethyl acetate and various aldehydes with marine, saline, and herbal character.

Chartier highlights fino’s aromatic “precision”—a result of “flor”-driven molecules that lend it both delicacy and tension. Manzanilla, aged in the coastal town of Sanlúcar, typically leans even more toward briny, sea spray notes thanks to local humidity and “flor” activity.

From a molecular standpoint, these wines are natural partners for foods that share salinity, umami, or aldehydic depth—such as shellfish, seaweed, cured ham, and even pickled vegetables. They don’t overpower; they amplify.

AMONTILLADO: NUTTY AROMAS AND UMAMI COMPLEXITY

Amontillado is a style born of transformation. It begins life under “flor”, like a fino , but then evolves through oxidative aging after the flor disappears. This dual nature gives amontillado a unique aromatic identity—combining the tangy, aldehydic freshness of biological aging with the deeper, nutty tones developed through oxidation.

François Chartier describes amontillado as “the diplomat between worlds,” with molecules such as acetaldehyde from the flor phase overlapping with sotolon, a compound formed during oxidative aging. Sotolon is powerfully aromatic even at trace levels, carrying notes of toasted nuts, curry, and aged cheese—compounds that are echoed in many umami-rich foods.

This molecular layering makes amontillado exceptionally versatile in pairings. From a scientific angle, it aligns with aged cheeses, mushrooms, roasted poultry, and complex broths—dishes where savory and nutty dimensions dominate. Its moderate weight and acidity also allow it to balance rich textures while intensifying flavor through aromatic resonance.

OLOROSO: DEEP, OXIDATIVE NOTES AND SPICES

Oloroso is the boldest of the dry sherry styles, shaped entirely through oxidative aging. Without the protective veil of flor, the wine evolves slowly in contact with oxygen, developing layers of aromatic richness.

François Chartier calls it “a sensory symphony of Maillard-derived molecules,” referring to the deep-roasted and nutty aromas that emerge during long cask maturation—think furfural, vanillin, and phenolic aldehydes.

These compounds are echoed in a wide range of robust ingredients: seared foie gras, braised oxtail, aged cheeses, or dishes enhanced with browned butter. The wine’s high glycerol content, warm amber hues, and generous alcohol create a plush texture, while its aromatic density complements spice-forward or umami-rich cuisines. Oloroso doesn’t just pair with food—it elevates it.

PALO CORTADO: THE BRIDGE BETWEEN ELEGANCE AND POWER

Palo Cortado is one of sherry’s most intriguing expressions—defined not by strict rules, but by the unique character it develops over time. Traditionally, it begins life destined for biological aging, but due to structural or sensory distinctiveness, it’s redirected to oxidative maturation, often after only a brief “flor” phase. The result is a rare style that marries the linear elegance and acidity of amontillado with the roundness and depth of oloroso.

From a molecular standpoint, palo cortado leans toward the oxidative profile—featuring compounds like phenolic aldehydes, furans, and lactones—while retaining a taut, refined structure. As Chartier puts it, “palo cortado is the winemaker’s sherry—mysterious, complex, and rare.” Its versatility lies in that equilibrium: it can elevate refined dishes such as veal sweetbreads, duck breast with fruit glaze, or mushroom-based broths, while also standing up to richer umami preparations. In molecular pairings, it acts as a subtle harmonizer—less showy than oloroso, but often more intriguing.

PEDRO XIMÉNEZ: SWEETNESS, DRIED FRUIT, AND DARK AROMAS

Pedro Ximénez (PX) is a wine of unashamed opulence—its sweetness derived from sun-dried grapes and its flavor shaped by time, concentration, and oxidative aging. The result is a velvety liquid layered with molasses, fig, coffee, and spice notes. From a molecular perspective, PX is a reservoir of Maillard reaction compounds—furfural, maltol, sotolon—and sugar-derived volatiles that evoke toffee, dried fruit, and dark chocolate.

This rich palette makes PX a compelling candidate for molecular pairing. “Both roasted coffee and aged sherry contain furfural and sotolon,” notes François Chartier. These compounds act as aromatic bridges in pairings with espresso-based desserts, roasted nuts, or even black garlic and balsamic-glazed preparations. The key is to match intensity and reinforce the wine’s core aromas.

At the same time, the wine’s natural acidity and phenolic structure can lend balance, preventing the pairing from becoming cloying. A well-chosen PX—served with restraint—offers more than indulgence. It offers depth, resonance, and the pleasure of aromatic déjà vu.

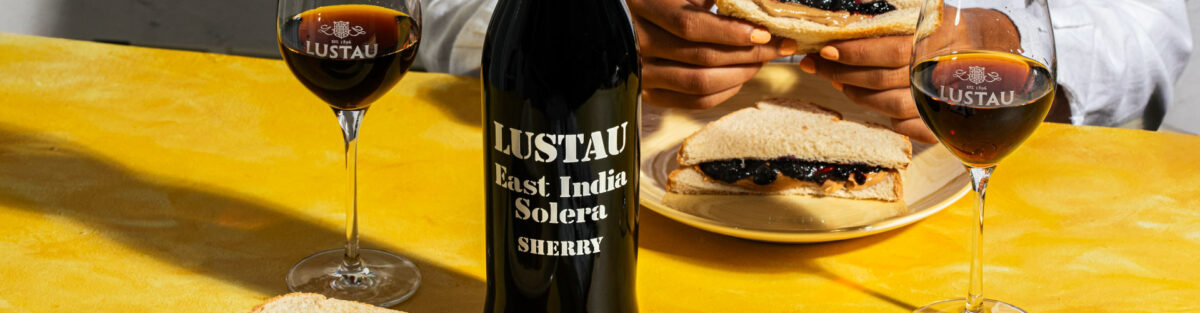

SWEET WINES AND CREAM SHERRIES: HARMONIES OF BALANCE

While often misunderstood, sweet and cream sherry wines are not afterthoughts—they are precisely blended wines that bring together the depth of oloroso or amontillado with the luscious sweetness of pedro ximénez or moscatel. The result is a layered, polished style that balances residual sugar with oxidative complexity.

From a molecular standpoint, these wines inherit a mosaic of volatile compounds: nutty aldehydes and Maillard-derived molecules from the dry base, combined with the dried fruit esters and caramel tones of the sweet component. “It’s a symphony of shared aromatic cues,” François Chartier might say—where sotolon, vanillin, and lactones evoke everything from toasted pecan to maple syrup.

Their versatility shines with pairings that straddle sweet and savory: foie gras terrine, aged Gouda, pecan pie, or spiced duck. They are also prime candidates for cocktail integration, where their layered aromas can soften spirits or elevate cream-based creations.

TRADITION MEETS SCIENCE: CLASSIC PAIRINGS, REIMAGINED

Some food and wine pairings feel so intuitive—so time-honored—that we rarely pause to ask why they work. Manzanilla with jamón ibérico, amontillado with grilled artichokes, pedro ximénez with dark chocolate: these are classics for a reason. But tradition, as François Chartier often reminds us, can also be a door into deeper understanding.

Molecular pairing invites us to decode the sensory logic behind these matches. By analyzing shared aromatic compounds, we can uncover the invisible threads that bind certain wines to specific foods—not by chance, but through chemistry. This doesn’t replace culture, emotion, or memory. It adds another layer.

In the sections below, we revisit some of the most emblematic sherry pairings through the lens of aroma science. The results don’t dismantle what we already know; they reinforce it—and, at times, offer entirely new directions for creativity in the kitchen.

WHY FINO AND JAMÓN IBÉRICO SPEAK THE SAME AROMATIC LANGUAGE

Some pairings are legendary. Fino and jamón ibérico have long stood at the summit of Spanish culinary culture—instinctively satisfying, endlessly praised. But what makes them work so well? Molecular analysis reveals the answer lies not only on the palate, but in the air between them.

Both fino and jamón ibérico contain key volatile compounds like hexanal, nonanal, and pyrazines—aromas evocative of roasted nuts, aged fat, and cured umami. These shared molecules create a kind of olfactory resonance. On a chemical level, the wine and the ham quite literally speak the same aromatic language.

The role of “flor” is crucial. During biological aging, the veil of yeast produces acetaldehyde and saline aldehydes, giving fino its crisp, briny character. These echo the savory, cured notes found in well-aged jamón, reinforcing one another in the glass and on the tongue.

The balance is precise: the wine’s acidity and freshness lift the ham’s richness, while its salinity sharpens the sweetness of the meat. It’s a dialogue of texture and scent—where tradition and science converge in a single, perfect bite.

AMONTILLADO WITH MATURE CHEESES: A MOLECULAR AFFINITY

Amontillado’s layered personality—combining the freshness of biological aging with the richness of oxidative development—makes it one of the most versatile partners for cheese. Its nutty, savory profile matches the intricate flavors found in aged wheels, especially those with crystalline textures and long affinage.

The result is a resonant, savory pairing where no element overshadows the other. Amontillado dry structure and lifted acidity balance the richness of the cheese, while the shared aromatic DNA creates a seamless sensory experience. This is less about contrast and more about elegant reinforcement—two aged expressions speaking the same flavorful language.

OLOROSO WITH GAME MEATS AND SPICES

Oloroso is the deep voice in the sherry choir—rich, oxidative, and resonant with layers of toasted walnut, citrus, leather, and spice. A wine born entirely under the influence of oxygen, it develops a powerful aromatic structure anchored by molecules like furfural, vanillin, and phenolic aldehydes, many of which also appear in Maillard-reaction-rich ingredients like seared meats and roasted spices.

These molecular intersections are why oloroso feels right at home with game. Whether it’s slow-braised venison, wild duck, or rabbit with rosemary and clove, the savory intensity and spice-laced depth of the dish mirror the wine’s own character. As Chartier notes, oloroso is a “sensory symphony” shaped by aging—and the dishes it elevates often share that same long-developed complexity.

Beyond the chemistry, there’s something soulful about this pairing. Take, for instance, a slow-braised venison stew with juniper and cloves: the wine’s roasted hazelnut and toffee notes echo the savory caramelization in the meat, while its firm structure tames the richness of the dish. The warmth of the oloroso deepens each bite, and its dry, layered finish leaves the palate refreshed. Together, they speak of patience, transformation, and the bold beauty that emerges when time is the main ingredient.

PEDRO XIMÉNEZ WITH CHOCOLATE AND ROASTED COFFEE AROMAS

Pairing pedro ximénez with dark chocolate or roasted coffee-based desserts is not just a question of indulgence — it’s an exploration of how sweetness and bitterness, warmth and depth, can intertwine on the palate. PX, with its syrupy texture and concentrated notes of dried figs, molasses, and caramelized nuts, meets its match in the toasted bitterness of high-cocoa chocolate or espresso-based sweets.

What makes these pairings compelling isn’t just shared richness, but complementary structure. The wine’s unctuous mouthfeel softens the tannic edge of dark chocolate and smooths the bitter contours of roasted coffee. Meanwhile, shared molecules like furfural and sotolon — often present in roasted, aged, or oxidized ingredients — amplify a sense of aromatic coherence.

François Chartier views these links as part of PX’s “aromatic generosity,” where the wine’s high concentration of Maillard-derived compounds allows it to build bridges to both sweet and savory dishes. Whether paired with flourless chocolate cake, tiramisù, or even a dark mole sauce, PX creates a deeply layered experience that feels almost orchestral in its harmony.

CONCLUSION: THE MOLECULES THAT UNITE SHERRY AND GASTRONOMY

In the world of wine and food, harmony is often described in poetic terms — balance, elegance, soul. But what if behind these intuitive sensations lies a precise aromatic code? Molecular pairing, as explored through François Chartier’s pioneering work, reminds us that gastronomy is as much about shared chemistry as it is about shared pleasure.

Sherry wines, with their layered profiles shaped by flor, oxidation, and long solera aging, offer a unique window into this world. Their aromas are not just beautiful — they’re instructive. And yet, the ultimate power of molecular pairing is not in its data, but in its generosity. It provides a framework for creativity, a lens through which chefs, sommeliers, and curious drinkers can reimagine pairings — not by convention, but by resonance.

At its best, this isn’t just science. It’s storytelling through flavor.